The Life of Pi--Yann Martel

reviewed by Jim Tschen-Emmons 1.25.2004

I

do not normally read bestsellers. This is not so much because of laziness in

reading, or a lack of acquaintance with current New York Times favorites, or

even out of some errant snobbery that believes anything popular vulgar (though

that is true enough in too many cases), but because I rarely see fiction titles

that immediately pique my interest there. Also, my reading list these days consists

largely of a backlog of titles-to-be-read that friends and family have urged

me to read for years, and this being January and the only month likely to see

me attempt let alone succeed in following any New Year's resolutions, I feel

I must start with those. Also, between these books, and those I must read professionally,

I normally cannot afford the luxury of the NYT Bestsellers. With Yann Martel's

_Life of Pi_, however, I made an exception.

I

do not normally read bestsellers. This is not so much because of laziness in

reading, or a lack of acquaintance with current New York Times favorites, or

even out of some errant snobbery that believes anything popular vulgar (though

that is true enough in too many cases), but because I rarely see fiction titles

that immediately pique my interest there. Also, my reading list these days consists

largely of a backlog of titles-to-be-read that friends and family have urged

me to read for years, and this being January and the only month likely to see

me attempt let alone succeed in following any New Year's resolutions, I feel

I must start with those. Also, between these books, and those I must read professionally,

I normally cannot afford the luxury of the NYT Bestsellers. With Yann Martel's

_Life of Pi_, however, I made an exception.

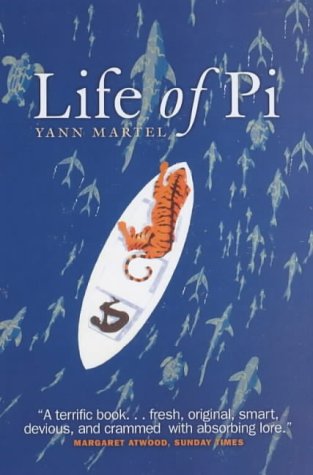

The plot seems very simple: a boy finds himself the only survivor of a sinking ship, he floats on the Pacific in a lifeboat, and has a tiger for a traveling companion. But there is so much more to this story than that. As the aged Indian man says to the narrator, this is a "story that will make you believe in God." While one's own reading may not produce such grand results (assuming one does not already believe in a deity or deities), one will not come away from this book without wondering about the divine, about the incredible nobility of humanity (especially in crisis), the place of people in the natural world, and the possibilities inherent in a world of faith, hope, and action.

Pi Patel-the Pi is short for Piscine (fr. "swimming pool")-is the happy, loving son of an Indian zookeeper in Pondicherry, a small place in what was French colonial India. He loves to swim, struggles in the wake of a popular older brother, and enjoys a very close relationship with Krishna. Pi's religious adventures, which comprise a large part of his pre-shipwreck life, are related in a funny, beautiful, and thought-provoking way. Pi, a devout Hindu, also becomes a devout Christian, _and_, a devout Muslim, much to the frustration of the respective religious guides and his parents. Yann Martel's depiction of Pi's meeting with these leaders is one of the most amusing parts of the book, but it is also a powerful statement about the nature of God, love, faith, and religious understanding and toleration. Pi's faith is a leitmotif throughout the book, and a powerful lesson in the human ability to hope.

After the shipwreck, we follow Pi as he sets about trying to survive. His determination becomes all the more impressive when he finds that the only other survivor, so to speak, is a Bengal tiger. Faced with such a conundrum, Pi falls back on his faith, his resourcefulness, and the knowledge he acquired growing up as the son of a zookeeper. Martel's masterful weaving together of two different strands of tenuous survival, one on the sea, and one in the face of a large, hungry, scared cat keeps one's interest and will, if one reads late into the night as I do, make one late for work. At issue here is more than the skillful maneuvering, chapter by chapter, of a scene that could become tiresome with a less capable writer; there are deeper currents, one that explores not only humanity's resourcefulness, but also our place in nature, what it is that separates us from other mammals, and what, in turn, we might learn from them.

Together with the religious questions behind Pi's

faith(s), the question of who we are and what we might

be keeps one reading. I will not lie to you, however:

Pi is on the waves for a long time, and there are

moments that are uncomfortable. In fact, there is

more than one place in this tale that will make you

wince, or look for land or distant sails. But like

Pi, we must hold on, see the trip through to wherever

it leads, and perhaps unlike Pi, enjoy the ride. The

reward is worth the effort.